Today, we FINALLY move away from the eastern continent for the first time since the War of the Confederation lecture. Today we learn about the War of the Pacific between Chile, Peru and Bolivia.

Top: Different territorial disputes between the nations of South America.

Top: Different territorial disputes between the nations of South America.

Bottom: Mariano Melgarejo

Chile had long had a rivalry with its two northern neighbors of Peru and Chile. By the 1870's, things were starting to reach a head. First, the causes as to how this war began.

The Atacama Desert may seem like a worthless desert, but the desert contained multiple incredibly valuable resources. The Atacama contained large quantities of sodium nitrate and high quality guano (Guano is bird poop btw, just in case you want to know what it is). Sodium nitrate and guano were key components in fertilizer and explosives, two things that were in high demand in Europe. By the 1840's the value of guano and nitrate sky rocketed, and the Atacama suddenly became a gold mine for Chile, Peru and Bolivia. Most of the Atacama was owned by Chile after Chilean miners moved into the area following the Chilean silver boom in the 1830's. Bolivia and Peru both claimed the Atacama as well, however, and relations between Chile, Peru and Bolivia began to deteriorate. Foreign powers even began to try and get rich from the Atacama, when Spain attempted to take the Chincha Islands from Peru in the 1860's.

During this period, Peru, Bolivia and Chile tried to establish alliances with each other or other nations in order to protect themselves from one another. In February of 1873, Bolivia and Peru signed a secret alliance against Chile. The treaty would remain secret until 1879. Argentina was asked to join the alliance due to their disputes with Chile over Araucania, Patagonia and the Magallan Strait. Initially, the Argentines seemed interested, but disputes between Bolivia and Argentina over the territories of Tarija and Chaco, as well as the Argentine fear of a Chilean-Brazilian Alliance, made the Argentine Congress reject the ratification of the treaty. Some historians believe that a reason why Peru developed an alliance with Bolivia was to prevent a proposed alliance between Chile and Bolivia. The terms of the treaty states that Bolivia would gain the Peruvian port of Arica, where most Bolivian shipping went to and fro from, and for Bolivia to cede Antofagasta to Chile. The Alliance proposed by Peru was more generous to Bolivia then the one presented by Chile, so thus the Bolivians signed the alliance with Peru instead.

In 1874, a boundary treaty between Bolivia and Chile was signed. The treaty stated that the boundary would be set at the 24th parallel south, but giving Bolivia the right to collect tax from territory between the 23rd and 24th parallels as well. In exchange for allowing the Bolivians to collect tax from their territory, the treaty also stated that all Chilean commercial interests and Chilean exports could not be given increased taxes for 25 years.

Other causes of the war are disputed. Some say that Chilean businesses virtually forced Chile to war in order to protect commercial interests in the Atacama, while others say that the war was premeditated by Peru in order to establish hegemony over the western coast of the continent. One of the better theories was stated by Frederick Pike. Pike's theory was that the situation in the Southern Andes was similar to the Mexican-American conflict in N. America, saying that Peru and Bolivia, economically and politically weaker than Chile, were envious of Chile, and that Chile itself also had beliefs that they had the power to expand northward into its northern neighbors.

The most evident cause of the war, however, involved the Anglo-Chilean Company named the Compañía de Salitres y Ferrocarril de Antofagasta (CSFA for short). The Chilean entrepreneurs of José Santos Ossa and Francisco Puelma founded the company with British capital and with aid from the London based Antony Gibbs and Sons, who were also shareholders in Peruvian guano and nitrate. They worked mainly in the Bolivian Atacama, and gained permission to mine there by Mariano Melgarejo, the Bolivian president at the time. From the company's foundation in 1866 to 1871, the company got incredibly rich, with even Chilean politicians investing in the company. That same year, Malgarejo was out of power in Bolivia, and the Bolivian government ended all contracts with the CSFA and asked the CSFA to renegotiate its contracts in 1872. The CSFA agreed to renegotiate, and gained a license from the Bolivian executive to exploit the resources of the Atacama for 15 years duty-free. The Bolivian parliament never agreed on giving the license, however, and a lawsuit against the CSFA began. The lawyers who claimed that the CSFA had to get permission from the Bolivian parliament first pointed to the law stating that it had to be accepted by parliament, while the lawyers supporting the CSFA pointed out that the same law also stated that the parliament only had to accept in conflict cases.

Meanwhile, the Peruvians wanted to gain a monopoly on nitrate and guano boom. The president of Peru, Mariano Ignacio Prado, was determined to give his country a monopoly on the incredibly profitable market of the resources. In 1876, Antony Gibbs and Sons became the consignee for the nitrate trade of the Peruvian government, and, in the same year, bought the company of El Toco from an auction decreed by the Bolivian government. The CSFA was the only main competitor of the Peruvian government, but it was a major threat to the economic interests of Peru. The Peruvian government tried to make Antony Gibbs and Sons persuade the CSFA to begin limiting its output of nitrate and guano, Henry Gibbs even told the CSFA that they would have administrative issues with the Bolivian and Peruvian governments if they did not limit their output. The CSFA refused to limit there output, despite multiple repeated attempts to try and persuade them to do so.

Meanwhile, in Bolivia, the Bolivian national congress agreed to impose a ten cents per quintal tax upon the CSFA in 1878. The CSFA challenged their tax, however, claiming it went against the boundary treaty of 1874, and the CSFA requested Chilean intervention in the situation. The CSFA believed the tax was an attempt by the Peruvian government to make the CSFA go out of business and for Peru to have the monopoly which they had wanted. The Chileans intervened, and demanded the Bolivian tax be lifted. The Chileans were especially upset because they had to relinquish their claims to the Atacama in the treaty of 1874. The Chileans warned the Bolivians and Peruvians that Chile would declare the 1874 boundary treaty null and void if the tax wasn't lifted. The Bolivians and Peruvians, having a secret alliance, challenged Chile and claimed that the tax was not related to the treaty and that the CSFA must be addressed in the Bolivian courts. They then revived the tax. When the CSFA refused to pay the tax, the Bolivian government confiscated their property and put the company for auction.

Upon hearing of the Bolivian confiscation of the CSFA's property, the Chileans dispatched one of their two ironclad warships to the area and occupied the vital Atacama port city of Antofagasta in February of 1879. 200 Chilean soldiers occupied the city with virtually no resistance. The occupying forces received a warm welcome, with celebrations from the Chileans in the port. The population of the port itself was ~95% Chilean. It was in Antofagasta that the Chileans discovered the secret alliance between Peru and Bolivia. The Chilean colonel at Antofagasta, Emilio Sotomayor, intercepted a letter from Bolivian president Hilarión Daza which was meant to be sent to Bolivian colonel Severino Zapata. The letter expressed Daza's concern of Chilean military intervention and briefly mentioned the secret alliance between Peru and Bolivia.

Peru tried to mediate between Bolivia and Chile in February, but Bolivia ended up declaring war anyways on the 27th (All though it wasn't publicly official until March). Despite the declaration of war, José Antiono de Lavalle, the Peruvian diplomat sent to mediate, proposed to the Chileans in Santiago that they withdraw and have the Atacama be ruled by Peru, Bolivia and Chile together. The Chileans refused, but did send a telegram to Lima requesting for Peruvian neutrality in the war, while Bolivia asked the Peruvians to activate the secret alliance. On March 23rd, 554 Chilean troops defeated 135 Bolivian soldiers and militia dug in at two bridges near the Topáter ford. The Battle of Topáter was the first battle of the war. When the government of Chile officially asked Lavalle whether the Peruvians and Bolivians were secretly allied, and if they were planning to aid Bolivia, Lavalle could no longer escape secrecy. He said yes to both. Chilean President Aníbal Pinto requested the Chilean legislature for a declaration of war upon Peru, which did occur on April 5th, 1879. The War of the Pacific had now begun.

Top: Recreation of the Battle of Arica.

Top: Recreation of the Battle of Arica.

Bottom: Battle of Punta Gruisa

The Atacama was mostly void of railroads and roads, as well as virtually void of water and was largely unpopulated, making it difficult to occupy by the armies of the warring nations. Thus, the warring nations needed naval supremacy in order to gain the upper hand against the other side. Here are some naval statistics:

Bolivian Navy:

No official navy, but Bolivian president Daza offered letters of marque to all Bolivian ships who were willing to fight for the Bolivians.

Peruvian Navy: Two ironclad warships:

Huascar and

Independencia. The

Huascar weighed a total of 1,130 tons, had a 1,200 horsepower engine, had a speed of ~11 knots, 4.5 inches of armor, and was made in 1865. The

Independencia weighed 2,004 tons, had a 1,500 horsepower engine, a speed of ~13 knots, 4.5 inches of armor, and was also made in 1865. They also had outdated wooden ships.

Chilean Navy: Two ironclad warships:

Cochrane and

Blanco Encalada. The

Cochrane weighed 3,560 tons, had a 3,000 horsepower engine, had a speed of ~12.8 knots, 9 inches of armor, and was made in 1874. The

Blanco Encalada had the same exact statistics. Like Peru, Chile also had some outdated ships.

The Chilean navy was better than the Peruvian navy in virtually every aspect. They were faster, had more armor, and were equipped with the latest technology due to being made later than the Peruvian ironclads.

The first naval move of the war was made by Chile, when they blockaded the Peruvian port if Iquique on April 5th, 1879. The

Huascar was able to break the blockade and sunk the wooden

Esmeralda of Chile's. Meanwhile, the Peruvian ironclad

Independencia chased the Chilean schooner

Covadonga at Punta Gruesa until the

Independencia collided with a rock and sank. While the blockade of Iquique was broken, Peru lost one of its two ironclads within one year of the war's beginning, severely weakening Peruvian naval capability. This also left an impression upon Argentina, who, seeing that the Peruvians had been dealt a major blow within the first year of war, decided to maintain a policy of non-intervention. The

Huascar, despite being outnumbered, held on for several more months against numerically superior Chilean forces. Other smaller battles took place, such as the capture of the Chilean transport ship

Rimac, which was carrying a cavalry brigade. This caused the Chilean chief of the navy, Admiral Juan Williams Rebolledo, to resign. He was replaced by Commodore Galvarino Riveros Cárdenas. In August, the Peruvians attempted, unsuccessfully, to capture the British ship

Gleneg at the Strait of Magellan which was transporting weapons to Chile. On October 8th, the Battle of Angamos proved to be the nail in the coffin for the Peruvian navy, as, after several hours of battle, the Chileans were able to capture the

Huascar despite attempts by its crew to scuttle it. After the Battle of Angamos, the remaining Peruvian naval units were kept in port. The Peruvians never faced the Chileans head to head at sea for the rest of the war, but they were able to explode the Chilean ships

Loa and

Covadonga.

With Chile gaining control of the seas, the land war now began. The first major military campaign of the war was the Tarapacá Campaign. 9,500 Chilean soldiers were escorted to Pisagua via steam transports. The army then moved south toward Iquique, and engaged 9,000 enemy troops at Dolores. The Chileans won and the Peru-Bolivian army retreated to Oruro while the Peruvians instead retreated to Tiliviche. The Chileans captured Iquique. A Chilean force of artillery and cavalry faced the Peruvians at Tarapacá (the town, not the province). The Chileans were repulsed, but the Peruvians retreated to Arica. The province of Tarapacá was now under Chilean occupation, denying the Peruvians 28 million dollars in income from the nitrate deposits of the province.

Large riots in Lima, the Peruvian capital, took place due to the repeated failure of the Peruvian armed forces. President Prado left for Panama with 6 million pesos on December 18th of 1879 to buy weapons, leaving his vice president, Luis La Puerta de Mendoza, in control for the time being. Before Prado came back, a coup d'etat led by Nicolás de Pierola overthrew the government and took power on December 23rd. Upon hearing of the coup, Bolivian president Daza left for Europe with 500,000 American dollars. Narcisco Campero became the new Bolivian president.

While the governments of both their enemies collapsed, the Chileans continued their campaigns. In November, the Chileans began the blockade of Arica, and sent out a reconnaissance force to Ilo, north of Tacna, in December. On February 28th, 1880, the Chileans landed 11,000 men at Ilo. They met no resistance until March 22nd when they engaged ~1,600 Peruvians at the Battle of Los Angeles. The Chileans won the battle, and resulted in the direct supply route between Lima and Tacna being cut off. Following the battle, only three Allied armies were left in Southern Peru. On May 26th, 14,127 Chileans fought 5,150 Bolivians and 8,500 Peruvians at the Battle of Tacna. The Chileans won the battle and the Allied army was completely destroyed. Now, the Chileans needed a major port in order to supply their men in Peru, and the only one near the armies was the Peruvian stronghold at Arica. On June 7th, the Chileans captured Arica and destroyed the last Allied forces in Southern Peru. The Tacna-Arica Campaign resulted in the severe weakening of the Peruvian military and the near destruction of the Bolivian one. The Battles of Arica and Tacna were the decisive battles of the war.

With the major areas of Souther Peru captured, the Chileans set their eyes on the North of Peru. In September of 1880, the Chilean government sent ~2,000 men under the command of Captain Patricio Lynch to land in Northern Peru and collect war taxes from wealthy landowners from the area. This was later referred to as Lynch's Expedition. The expedition landed in Chimbote on the tenth, and spread to various other cities in the far north. They collected, in local currency, $100,000 from Chimbote, $10,000 in Paita, $20,000 in Chiclayo, and $4,000 in Lambayeque. Those who did not pay the tax had their property destroyed. While the Peruvian government stated that it was an act of treason to pay the Chileans, most landowners payed anyway to protect their property. Lynch's expedition was protected by international law, despite Peruvian claims that it went against international law. The Lynch Expedition proved that the Peruvian military no longer had the capability to defend the country from Chile, but they still weren't willing to sue for peace. The Bolivian treasury was empty, the militaries of both countries virtually annihilated, but they refused to accept any peace, the Bolivian congress even voted to continue the war in June of 1880. The United States of Peru-Bolivia was also proclaimed by Peru, but it was realistically still two nations and not one together. The Chileans now needed to give the Peruvians a blow large enough to force them to consider unconditional surrender: They were going to occupy Lima.

The Chileans didn't have enough ships to transport their forces from Tacna and Arica to Lima, so they had to do land one division per trip. They began landing forces at Pisco, ~300 miles south of Lima. On November 19th, 1880, there were 8,800 men at Pisco; by December 15th, there ~16,400 total Chilean forces at Pisco. They then marched North toward Lima. The Chileans were now fighting local militia and civilians in Lima, there were no professional soldiers in the city. Pierola, Peruvian president, ordered the construction of two defensive line in the city, one at Chorrillos and another at Miraflores, both of which were just outside the city. The Peruvian citizen army numbered ~25,000-32,000 men. On January 13th, 1881, the 16,400 professional Chilean soldiers charged against up to 32,000 Peruvian militia at the Chorrillos Defensive Line. The fighting was intense, as the Peruvian militia fought to the end, fighting for their country, spurred on by patriotism. The Chileans were also fighting for their country and were also spurred on by patriotism, resulting in brutal fighting between the two patriot armies. The untrained Peruvian militiamen quickly became disorganized and fell back to Miraflores. The entire Chorrillos line collapsed within a matter of one day, and Miraflores followed two days later. The Chilean military entered Lima on January 17th. The remnants of Peruvian navy were scuttled in order to prevent the capture of the ships by Chile.

On July 23rd, 1881, Argentina and Chile signed a boundary treaty. Argentina and Chile had a long territorial dispute over Patagonia and Araucania, to the extreme south of the continent. Chile was previously not willing to negotiate for anything less than all of Patagonia and Araucania, but during the War of the Pacific, the Chilean government was worried of possible Argentine intervention. While the Argentina was officially neutral, they did allow for weapons to be transported to Bolivia using their land and tried to exert influence over the USA and Europe to officially renounce Chile's actions. Thus, Chile and Argentina went to the negotiating table in order to agree on the boundaries of the nations. Ultimately, the Chilean government agreed to relinquish its claims to eastern Patagonia in exchange to own the strait of Magellan and thus land connecting to it (Thats why Chile is so long). This virtually ended all chance of Argentina getting involved in the war.

The Peruvian state now collapsed, and society teared itself apart. Peruvian president Pierola left the country in December, leaving no head of state in charge of the country. Violence ensued, mainly based off of race or social class. Peruvian citizens attacked Chinese grocery stores, Afro-Peruvians attacked the wealthy, and Indian immigrants left for the highlands. The fall of Lima did not force the Peruvians to peace, however, and multiple local Peruvian caudillos (it means leader in Spanish, but these caudillos were local strongmen) lead a defensive war against the Chileans. These Peruvians launched a guerrilla campaign against the Chileans in the interior, and the ensuing campaign was brutal, prolonged, and futile campaign. The first attempt to end the rebels was by Ambrosio Letelier, who, with 700 Chileans, attempted to root the guerrillas out of Huanuco and Junin. The campaign was very short, and Letelier withdrew his forces after heavy casualties. In January of 1882, 5,000 Chileans, led by Lynch, began the 1882 Sierra Campaign, meant to to annihilate the guerrillas in the Mantra Valley. Lynch's forces were decimated due mountain sickness, cold and snow. On July 9th, the Peruvians won the Battle of La Concepcion. This battle resulted in the withdraw of Lynch's forces from the Sierra. Lynch attempted one last offensive in April of 1883 against the Peruvians in the Sierra. On July 10th, the Chileans won the Battle of Huamachuco, virtually ending all organized Peruvian resistance in the war.

On October 28th, 1883, Peru and Chile signed the Treaty of Ancón was signed, ceding the province of Tarapacá to Chile and for a plebiscite to be held in the cities of Arica and Tacna to determine which country the cities would wish to be absorbed into. The Chilean and Peruvian governments argued for decades over the terms of the plebiscite, and the issue finally ended in 1929 after intervention by U.S president Herbert Hoover. Hoover was able to make a deal which pleased both parties, where Chile annexed Arica and Peru re-annexed Tacna. This second agreement made by Hoover was made official with signing of the Treaty of Lima. In 1884, Bolivia and Chile signed a definitive peace treaty, despite not having have fought against each other in a major battle since 1880. The Treaty of Valparaiso was signed between the two nations, and the Treaty of Peace and Friendship in 1904 made this treaty permanent. The Treaty of Valparaiso stated that the entire Bolivian coastline was ceded to Chile, and with it the major cities of Antofagasta and the regions rich resources. In return, Chile built the Arica-La Paz Railway line which connected the Bolivian capital to the Chilean port city of Arica, and guaranteed freedom of passage for Bolivian commerce.

Top: The Peruvian Wart, or Carrions Disease

Top: The Peruvian Wart, or Carrions Disease

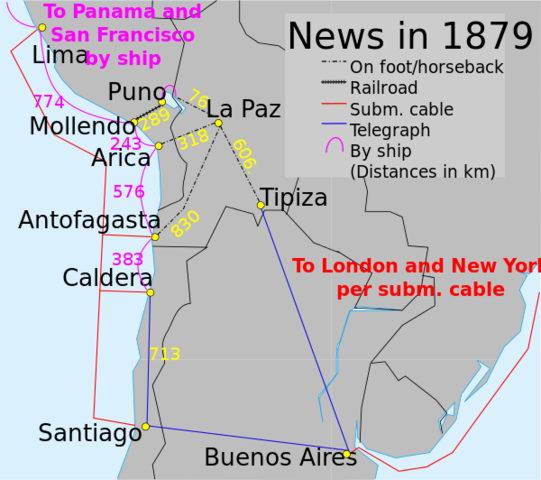

Bottom: Use of communication during the war.

The War of the Pacific proved to be one of the most important conflicts in modern war. The war saw the use of steam ships, breech-loaded rifles, improved artillery, remote-controlled mines, torpedoes, effective landing crafts, torpedo boats, and amour-piercing shells. The war also saw the use of improved technology for communication. While the Chileans would still use methods such as horseback to convey messages, the Chileans also used innovative ways to communicated with its vastly spread out army. They used railroads on land, submarine cables in the ocean, by naval supply units, and the telegraph. The war, aside from being an incredibly modern war, demonstrated the power of a strong navy. Due to the harshness of the Atacama desert, marching units through the area would result in massive casualties due to heat exhaustion, dehydration and disease. Thus, control of the seas was necessary for victory in the war. Chilean naval supremacy meant that the Chileans could make amphibious landings in Peru and avoid the Atacama completely. If Chile lost the Naval War, it is very possible that Peru and Bolivia could have won the war. The war became an inspiration for Alfred Thayer Mahan's

The Influence of Sea Power upon History.

Disease was rampant in the war, killing many on both sides. This war also gave a nickname to Carrion's Disease, as Chilean soldiers who caught the disease called it "The Peruvian Wart" due to the large warts on the skin after catching the disease and due to their resentment towards the Peruvians. Carrions Disease was rampant during the Sierra Campaigns.

Upon the war's beginning, a total of 30,000 Chilean citizens were expelled from Peru and Bolivia within 10 days and sent to the port of Antofagasta. 7,000 of the Chileans expelled from Peru later joined the Chilean military to fight against Peru. Peruvian and Bolivian citizens were not expelled from Chile. Both sides claimed that the other had killed wounded soldiers, but there is no direct evidence to support these claims. In Peru, multiple atrocities against ethnic minorities began once Peruvian society collapsed, as many disenfranchised Peruvians killed Chinese, Indian, or Black Peruvians. In terms of warfare, both sides were found to have followed the Geneva Convention's rules of war and never violated any laws of war.

The War of the Pacific was both a war which built nations and brought other ones down. The war became a legend in Chile, as the war asserted their hegemony over the region and their power on the continent. The War of the Pacific built up a Nationalistic sentiment in Chile, and the War of the Pacific is often recreated in Chile. In Peru and Bolivia, both countries fell into heavy debt and resentment built up against their southern neighbor. To this day, Chilean relations with its northern neighbors have never improved.